In my home of Santa Barbara, California, there is a summer group ride on Tuesday nights called “Views and Brews.” As the name suggests, the ride climbs 9.5 miles and 3,400 feet up into Los Padres National Forest, whereupon riders usually crack a beer, soak in coastal scenery, and then descend back into town. The climb is fairly hard, but the pacing is easy. The only thing that ever makes the effort challenging is the heat.

Southern California can get toasty in the summer (especially inland), and the roads are extremely exposed. This has led to considerable discussion about optimal clothing for hot weather riding among Views and Brews acolytes. How should one dress for a hot weather riding?

Conventional wisdom says dark colors are hot and light colors are cool. But then why are so many pro cycling teams wearing dark colors? In a sport where people add carbon nanotubes to their chain lube to save half a watt at 40kph, why wouldn’t everyone wear white? Is the light tint of a yellow jersey a competitive advantage?

This question seems simple but turns into a rabbit hole quickly. In the real world, there are a million factors to consider: Type of fabric, color of fabric, how much you sweat, and how fast you’re going. Plus, consider ambient temperature and solar radiation. Designing an experiment that accounts for all these variables at once is challenging to say the least, and the results will depend massively on environmental conditions as well. All this to say, there’s no one answer to this question, but there are principles we can learn from, so The Pro’s Closet teamed up with some thermal imaging engineers and sports scientists to do a simple experiment to give you a little insight into what jerseys are best in the hot sun.

These are not real-world conditions. We didn’t have access to a wind tunnel. This experiment has not been replicated or peer reviewed. I wouldn’t even call this “science,” but the results are interesting.

If you just want the TL;DR it might go like this: Wearing light colors in the sun could help a little. Wearing light colors in the shade probably doesn’t help or could even be hotter. Sweating and airflow matter a lot.

Keep reading to find out why Ineos riders probably aren’t stressed about their navy blue kit.

Meet the jerseys

We tried to include a variety of different brands, materials, and colors in this test so we could compare things like wool vs synthetic, white vs black, or Specialized vs POC. We tested 18 different jerseys, (9 of which are available at The Pro’s Closet). Here are the contenders.

Five synthetic Mavic jerseys: White, Red, Grey, Black, and gradient

- Mavic Essential Jersey, white - $79

- Mavic Essential Jersey, black - $79

- Mavic Essential Jersey, haute red - $79

- Mavic Cosmic Graphic Jersey, raven - $79

- Mavic Cosmic Jersey, gradient white - $79

Material: 89% PES, 11% EL

Two wool jerseys

- Mavic Essential Merino jersey, magnet - $123

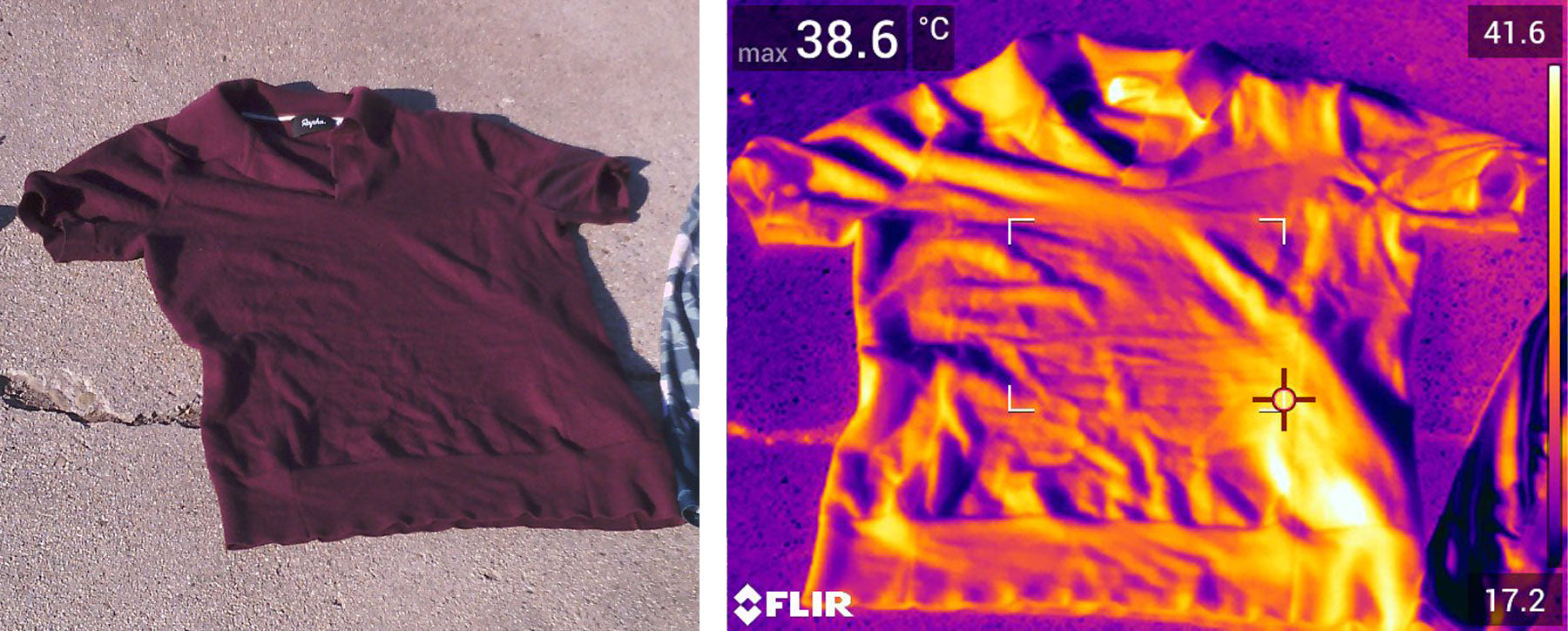

- Rapha Merino Polo, women's maroon - $115

Material: Merino Wool and PES blend

Two synthetic POC jerseys

Material: 100% PES

Four cheap jerseys from Amazon

- BERGRISAR Basic, white - $20

- BERGRISAR Basic, grey - $19

- Santic Cycling, white pattern - $40

- Weimostar - $22 (Black/white bars color no longer available)

Material: ~100% PES

Three jerseys from other cycling brands

- Rapha Core Jersey, black - $80

Material: 100% polyester

- Specialized SL Air, black/white - $120

Material: Specialized VaporRize (Specialized, the kings of marketing, use some proprietary blend of synthetics in their jersey. I can’t figure out exactly what the makeup is, but the internet says it’s made of recycled coffee and polyester.)

- Specialized Men's SL Race Logo Jersey, orange - $180

Material: Specialized VaporRize

The setup

We set all 18 jerseys out in direct sunlight on top of a cement driveway. The ambient temperature was 73 degrees Fahrenheit (22.7 C). We waited 10 minutes for the jerseys to heat up and reach equilibrium.

We then took a series of temperature readings from each jersey using a thermal imaging camera provided by FLIR Thermal Imaging and operated by Ted Conrad, the Sr. Principal Cryocooler Engineer at FLIR, and vaunted Views and Brews regular.

The camera, known as the E75, takes false color images to show how hot or cool a surface is. It reads up to 1,000 degrees Celsius and has laser-assisted auto focus — irrelevant to this experiment, but pretty cool.

“The core of the camera is a microbolometer that is sensitive to infrared radiation,” explains Conrad. Infrared radiation is electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength too long to be visible with the naked eye and is experienced by humans as heat. The camera can see what our eyes cannot.”

We took a number of readings for each garment. For jerseys that were a solid color, where the temperature was fairly consistent across the garment, I recorded the highest reading in the following table. For jerseys that were multiple colors and temperatures were not consistent, I recorded several readings. More on this in a bit. Finally, we sprayed each jersey with water from a spray bottle and recorded the temperature again.

Here are some examples.

This is a bunch of the jerseys laying out on the pavement. Cool colors are dark. Warm colors are light. The temperature is recorded at the crosshair. Here you can see that the cement in full sunlight was 19.2 degrees.

Here’s the white BERGRISAR Men's Basic Cycling Jerseys. It was one of the coolest jerseys in the whole experiment, except for its zipper, which, at 46.9 degrees C, was the single hottest thing we measured all day. It’s black, it’s metal, and it’s not covered up by any fabric like the zippers on some of the other jerseys.

Show me the data

Here’s a table showing all the temperatures we recorded. Numbers are in Celsius because that’s what the camera was set to, and we didn’t know how to change it.

| Jersey | Spot temp 1 | Spot temp 2 | Spot temp 3 | Temp after wetting |

| Specialized SL Air (black/white) | 27.6 | 26 | 11.6 | |

| Rapha Core (black) | 34.5 | 12.1 | ||

| Specialized Men's SL Race Logo Jersey (orange) | 26.2 | 11.2 | ||

| Santic Cycling Jersey (winter camouflage) | 24.2 | 38.3 | 31.7 | 11.1 |

| Weimostar Cycling Jersey (black/white bars) | 35.9 | 30.1 | 14.1 | |

| BERGRISAR Basic Cycling Jersey (grey) | 36.9 | 14.6 | ||

| BERGRISAR Men's Basic Cycling Jerseys (white) | 19.6 | 46.9 | 13.1 | |

| Machines for Freedom women's longsleeve (flower print) | 34.4 | 34 | 12.5 | |

| Rapha Merino polo women's (maroon) | 38.6 | 16.2 | ||

| POC women's essential road logo jersey (black) | 32.9 | 12.2 | ||

| POC Women’s Essential Road Logo Jersey (teal) | 24.9 | 33.1 | 11.5 | |

| Mavic Essential Jersey (black) | 37.2 | 33.1 | 14.1 | |

| Mavic Essential Jersey (haute red) | 34.9 | 11.9 | ||

| Mavic Essential Jersey (white) | 21.1 | 10 | ||

| Mavic Cosmic Gradient Jersey (gradient) | 29.3 | 26.4 | 24.4 | 15.4 |

| Mavic Cosmic Graphic Jersey Raven (dark grey) | 38.8 | 17 | ||

| Mavic Essential Merino Jersey Magnet (grey) | 39 | 41 | 12.3 | |

| TPC Giordana Scatto Pro SS Jersey (black) | 31.2 | 12.8 |

Analysis: Dry conditions

Above all, color absolutely makes a difference. Darker jerseys were consistently hotter than lighter jerseys, regardless of brand or material. The Mavic Gradient Jersey illustrates this perfectly. You can easily see how much hotter the dark bands are than the light.

In case you want to keep your shoulders cool, but your tummy toasty!

The two wool jerseys were among the hottest of all, but without a lighter color wool jersey to compare with, it’s hard to say that wool is definitely hotter than synthetics. Certainly, dark wool jerseys are hot in the sun.

This is the Rapha Merino Polo Women’s. Muy caliente.

This is the Rapha Merino Polo Women’s. Muy caliente.

On the other hand, the white jerseys were markedly cooler than the darks. The white Mavic Essential Road clocked in at 21.1 degrees Celsius. That’s almost twice as cool as the hottest jersey, the Mavic Essential Merino in grey.

Very cool, very modern.

Very cool, very modern.

Even the cheapo white jerseys from Amazon were very cool (if you don’t count the zippers and the black side panels). The cheap dark ones were no warmer than jerseys that cost 10x as much. The coolest jersey in the whole experiment was the white BERGRISAR Men's Basic Cycling Jerseys at 19.6 degrees Celsius.

This jersey had the hottest (zipper) and coldest (white fabric) temps recorded in the dry phase experiment. That should tell you that color is important for a dry jersey.

This jersey had the hottest (zipper) and coldest (white fabric) temps recorded in the dry phase experiment. That should tell you that color is important for a dry jersey.

Analysis: Wet conditions

Along with the importance of color, the big takeaway here is just how potent evaporative cooling is. Sweating works! Almost every jersey decreased in temperature by at least 50% when wet. The grey Mavic Essential Merino jersey went from 39 degrees Celsius to 12.3, that’s more than a 3-fold difference. The biggest temperature drops came from jerseys that were hot to begin with. The smallest came from the white BERGRISAR Men's Basic Cycling Jersey, which saw only a 50% reduction in temperature when wet.

Moisture is a real equalizer here. The range of temps observed in the dry phase of the experiment was 19.4 degrees C. For the wet phase, the range was just 6.2 degrees. Plus, the hottest wet jersey (maroon Rapha Merino polo women's) was still 4.9 degrees cooler than the coolest dry jersey.

The bottom line: Color matters drastically less if you’re sweating or pouring water on your jersey. A jersey that effectively wicks moisture is probably better than a light color fabric in sweaty real-world conditions. However, it doesn’t hurt to have both.

The Specialized Men's SL Race Logo Jersey was one of the coolest jerseys in both phases of the experiment, clocking in a chilly 11.2 degrees Celsius when wet. It must be the coffee grounds.

The Specialized Men's SL Race Logo Jersey was one of the coolest jerseys in both phases of the experiment, clocking in a chilly 11.2 degrees Celsius when wet. It must be the coffee grounds.

What does all this mean for real world conditions?

The obvious elephant in the room is wind. A jersey sitting on a driveway doesn't benefit from air flow. Ride a trainer without a powerful fan blasting in your face to quickly see how much difference air flow can make in performance. The experts agree that wind is only going to magnify the effect of evaporative cooling. Jersey color pales in comparison to the importance of moisture wicking. Sure, dry jerseys sitting in the sun may present gigantic temperature differences, but in real world conditions, those differences are going to be small to vanishingly small.

“All these effects probably lead to reduced heat,” says Emiel DenHartog, a textile engineer at NC State University. “For the actual effect in realistic environments, you won’t find [these kinds of temperature differences].”

“In cloudy conditions, it might actually flip, and the dark colors are better,” says DenHartog.

Making this equation even more complicated, however, is the fact that the energy radiating from the sun is, on average, not the same wavelength as the energy radiating from our bodies and wavelength matters. The sun emits radiation across UV, visible, and infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Humans emit radiation only in the infrared.

There are some brands that have touted cool dark colors, by creating fabrics that reflect a lot of wavelengths in the near infrared, while looking dark in the visible part of the spectrum. This is one more reason why color can’t tell you everything.

A garment could theoretically reflect the shorter wavelengths from the sun and absorb and transmit longer wavelengths from the body, more like a one-way mirror. But then again, you’d be absorbing those same longer wavelengths from the incoming sun now. Trying to calculate the exact radiation balance of a given piece of fabric is very fun!

So how should we actually dress if we’re trying to stay cool?

In hot, sunny places, lighter colors can’t hurt, but they might not help as much as you imagine. Light kit is especially helpful at the beginning of a ride, before you’ve started sweating, or on climbs, where there’s less airflow. If you’re racing a 10-minute hill climb with an average grade of 22% in the Arabian Desert, go for a white jersey. If you’re racing on forest roads on a cloudy day, it probably doesn’t matter what color your jersey is, and your brightest white could even be a little hotter.

The most important thing that a jersey can do for you is wick away sweat. A good synthetic jersey can even be better than nothing at all in some cases (sorry triathletes!). Because the capillary action sucks up a sweat droplet and disperses it across a larger surface area, sweat from a jersey can actually evaporate more quickly than from bare skin. This specific advantage only lasts until your jersey is saturated, obviously, but if you’re sweating that hard some of the droplets are probably rolling off your bare skin anyway.

Will any of this knowledge make me the fastest guy on the group ride? No. Will it make me slightly more comfortable on a hot ride? Possibly. Will it allow me to stop wondering about this question and enjoy the ride more? Yes.

Nerdy deep-dive: What about emissivity?

Shiny objects can reflect energy rather than actually emitting it as heat, throwing a bit of a wrench into measuring the temperature with a thermal imaging camera like the one we used. This is something that you should control for in an experiment like this. We did not. This experiment operates under the assumption that all the jerseys have the same emissivity value. This is not great form on our part, but even the shiniest fabrics, fortunately for this experiment, are not very reflective: A 2019 study in Textile Research found that cotton, nylon, and polyester all had thermal emissivity values around 0.88, meaning that 88% of the energy they were emitting was actually heat and not reflected. Because nearly all of the jerseys in our experiment were largely polyester, they should have extremely similar emissivity values.