Note: Before we dive into this bike, this IS NOT Greg LeMond's actual 1989 Tour de France TT bike. It would be cool if it were, but we’re not that lucky! This bike is a replica put together by a passionate collector and it’s currently on display in TPC’s Vintage Bike Museum.

Due to the 2024 Paris Olympics, this year's Tour de France didn’t finish with the traditional sprint stage on the Champs-Élysées. Instead, it ended with a time trial in Nice.

The last time the Tour finished with a time trial was 35 years ago when American Greg LeMond layed down an unbeatable time to secure his second Tour de France win by only 8 seconds. Until this year's epic Tour de France Femmes, where Kasia Niewiadoma beat Demi Vollering by only 4 seconds, it was the closest winning margin in Tour history. For many fans, LeMond's surprise victory is still one the greatest Tour de France finales of all time.

Besides the incredibly close finish, LeMond’s 1989 win was notable because he rode a TT bike equipped with triathlon-style aero bars to give him and edge over his French rival, Laurent Fignon. At the time, it was revolutionary, and it cemented LeMond’s status as a cycling legend:

How the 1989 Tour de France Was Won

In 1987, LeMond went from the defending Tour de France champion to a gunshot victim. A hunting accident had left 35 shotgun pellets in his body, including three in the lining of his heart and five more embedded in his liver. Many questioned if he would ever return the same caliber of rider he once was.

LeMond was not a favorite coming into the 1989 Tour. He had moved to ADR, a relatively weak Grand Tour team, and scored sub-par results in his lead-up to the Tour. He actually planned to retire after the 1989 Tour and was hoping just to finish in the top 20.

However, he raced surprisingly well in the opening stages, even winning the stage 5 individual time trial on his new Bottecchia TT bike. He rode himself into form, and by the time the race entered the mountains, he and two-time Tour-winner, Laurent Fignon were engaged in battle for the Yellow Jersey.

Coming into the final stage, LeMond trailed Fignon by 50 seconds. The traditional sprint finish on the Champs-Élysées was replaced with an individual time trial, but it was a short 25 km course, and he was not expected to be able to make up the deficit. LeMond would have to gain two seconds per kilometer, which seemed improbable against Fignon, who was one of the best time trialists in the world.

Greg LeMond on his race-winning TT bike.

Greg LeMond on his race-winning TT bike.

Lemond had a plan though. He had done wind tunnel testing in the off-season and perfected his riding position. He also put a set of triathlon-style aero bars on his bike, and an aero helmet on his head. His critics called these devices ugly, unnecessary, dangerous, and even maybe illegal.

Regardless, LeMond was able to hold a much more aerodynamic position and win the stage. More importantly, Fignon finished 58 seconds slower, giving LeMond the win.

LeMond could hardly believe it. His wife and team went crazy while Fignon collapsed in shock on the pavement. With an average speed of 54.545km/h (34.52mph), this was the fastest time trial ever ridden in the Tour (until Chris Boardman in 1994).

LeMond’s Bottecchia TT Bike

LeMond's 1989 win popularized the use of aero bars and aero helmets in time trials. This sort of equipment likely would have taken off anyway, but winning in such a spectacular fashion definitely accelerated TT development in the ‘90s.

LeMond’s steel-framed Bottecchia was similar to most other time trial bikes in the 1989 Tour de France. It had aero-shaped frame tubing and it was set-up as a “funny bike” with a 650b front wheel and Mavic rear disc wheel. Funny bikes earned their name because their aggressive, raked stance drew comparisons to American funny car dragsters.

Funny bike designs emerged in 1984 with Francesco Moser’s hour record bike. The reduction in height at the front (typically achieved with a 24” or 650c front wheel) was intended to reduce aerodynamic drag. A standard 700c wheel was used in the rear as it had less rolling resistance and didn’t require excessively large chainring tooth counts to obtain the desired gear ratios. Eventually, the UCI outlawed such designs in 1996.

LeMond’s ADR team used the “Tout Mavic” drivetrain which was designed to be more reliable and serviceable than the competition. The Tout Mavic rear derailleur, for example, could be rebuilt with new springs, pivot pins, and bearings in a matter of minutes. Sean Kelly used Tout Mavic to win at Paris-Nice, Liège–Bastogne–Liège, and an incredibly muddy Paris-Roubaix in 1984.

For the final time trial, Lemond used a 55t big ring on a Mavic “Starfish” crankset paired with a 7-speed 12-18t Regina Extra America freewheel with 1-tooth jumps between each gear.

The rear disc wheel is a Mavic Comete carbon disc wheel. In the 1970s, Mavic engineers discovered that a lenticular-shaped wheel (i.e., biconvex rather than flat) sliced through the air faster. Under some wind conditions, the lenticular flanges of the wheel could even create negative drag, increasing speed and acceleration. The early versions of the Comete were made of fiberglass.

The rear disc wheel is a Mavic Comete carbon disc wheel. In the 1970s, Mavic engineers discovered that a lenticular-shaped wheel (i.e., biconvex rather than flat) sliced through the air faster. Under some wind conditions, the lenticular flanges of the wheel could even create negative drag, increasing speed and acceleration. The early versions of the Comete were made of fiberglass.

Mavic debuted the Comete carbon fiber disc wheel at the 1984 Tour de France. The rim and hub were joined together with two specially shaped carbon discs and it was the first commercially available disc wheel. Other manufacturers followed Mavic’s lead, but without the same aero expertise, many designed flat discs that didn't reduce drag as much as the lenticular-shaped Comete.

What really set LeMond’s Bottecchia apart, however, was the addition of Scott clip-on aero bars designed by Boone Lennon. Lennon was a bicycle racer and a coach for the US alpine ski team. He was heavily involved with wind-tunnel testing for downhill skiers, so he understood the importance of aerodynamics. He developed the first aero bar prototypes with help from an engineer named Charley French.

The Scott aero bars were made from a shaped alloy tube with forged clamp ends and foam elbow rests. They weren’t light, and added nearly a pound to LeMond’s TT bike. It was worth it though, since wind tunnel testing showed the bars could save 90 seconds over a 40km time trial.

If aero bars were so fast, why was LeMond the only one using them at the Tour in 1989? Scott Sport’s vice-president, Pascal Ducrot, explained:

If aero bars were so fast, why was LeMond the only one using them at the Tour in 1989? Scott Sport’s vice-president, Pascal Ducrot, explained:

“At that time bicycle racers were not noted for their forward thinking, and in the beginning no racer wanted to try the bars. On the other hand, it was quite easy to convince the pro triathletes. Many of them were using these bars in 1987 and bike split times began to improve drastically. After showing him these triathlete results, Boone was able to convince Greg to try the Aerobars.”

A New Era

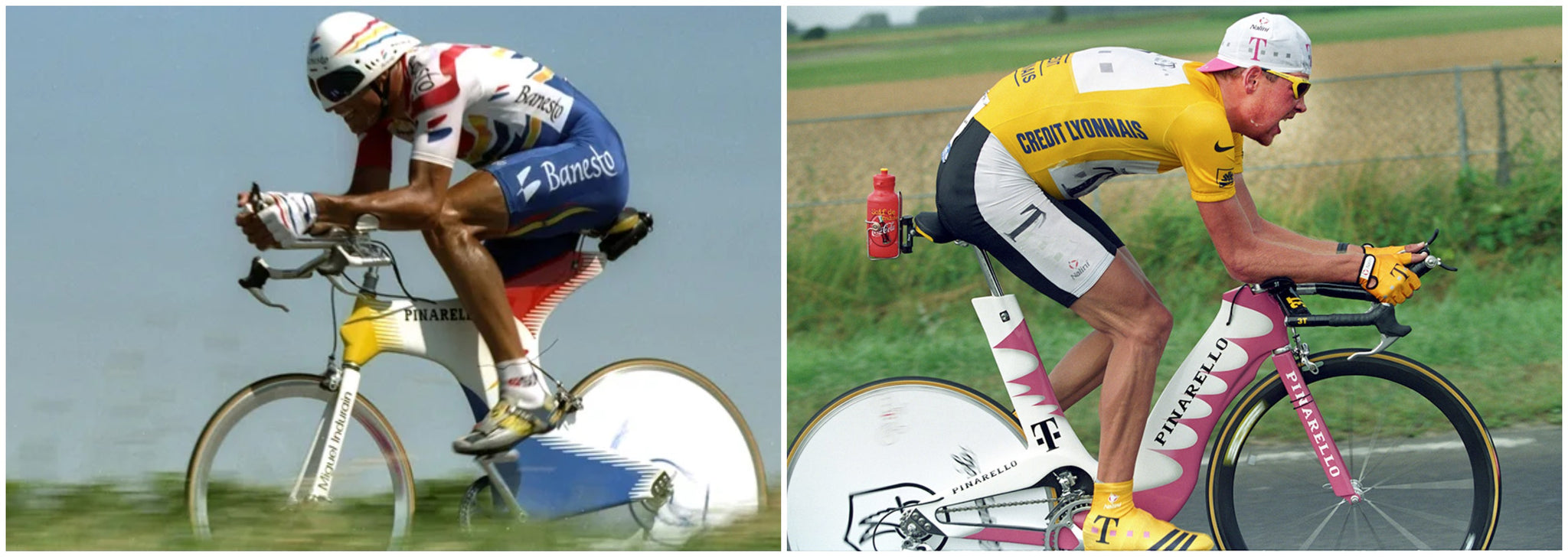

Aero helmets and aero bars were in. Miguel “Big Mig” Indurain (left) and Jan Ullrich on Pinarello time trial bikes. TT tech got crazy in the '90s.

Aero helmets and aero bars were in. Miguel “Big Mig” Indurain (left) and Jan Ullrich on Pinarello time trial bikes. TT tech got crazy in the '90s.

LeMond’s victory ushered in a new era of time trialing in pro cycling, where aerodynamic efficiency was just as important as strength and skill. It started a technological arms race that’s still being fought today as companies make each new bike or component slightly more aero than the last.

While aero bars were the focus of Greg LeMond’s victory in the final time trial of the 1989 Tour de France, there was a lot more than that at play. Laurent Fignon was suffering from saddle sores and showed up late to the start, which affected his performance. Some have also speculated that Fignon’s long ponytail flailing in the wind was much less efficient than LeMond's Giro aero helmet.

LeMond also had a mental and tactical advantage going into the final stage. LeMond had nothing to lose. Fignon also congratulated LeMond on his second-place finish the day before the final time trial. To LeMond, that was the moment Fignon lost. Fignon was overconfident and too relaxed.

LeMond went flat out at the start and told his team car not to give him time checks. He was going to give it absolutely everything, no matter what. Fignon, on the other hand, started with a much more relaxed pace. By the time he realized he was losing time, it was too late.

Reportedly, Fignon never stopped grieving his 1989 loss, and it haunted him long after his career ended. In his autobiography We Were Young and Carefree, Fignon recalled an encounter with a fan:

"Ah, I remember you,” the fan said. “You're the guy who lost the Tour de France by eight seconds!"

"No, monsieur,” Fignon replied. “I'm the guy who won the Tour twice."

It's a bit tragic that a two-time Tour de France winner, a rider who won nearly 100 races in his career, is remembered most for his greatest defeat. It is drama like this, however, that makes me love the sport so much.