Dropper posts, extra-long reach, coil shocks, 29” wheels, tire inserts — I’ve always been quick to try any tech that claimed to improve downhill performance. Mountain bikes equipped with reduced-offset suspension forks started getting buzz a couple of years ago. Hungry for more speed, I was quick to buy a new fork and test it out. Was it good? Yes. Did it change my world? Well, not quite.

I’ve studied the science and switched back and forth between reduced offset and “traditional” 51mm offset 29er forks on my own bikes. If you're interested in trying a reduced offset fork, this article is for you. Let's find out how fork offset affects your ride, why reduced-offset forks are becoming popular, and how riding a reduced offset fork feels to the average Joe (me).

What is fork offset?

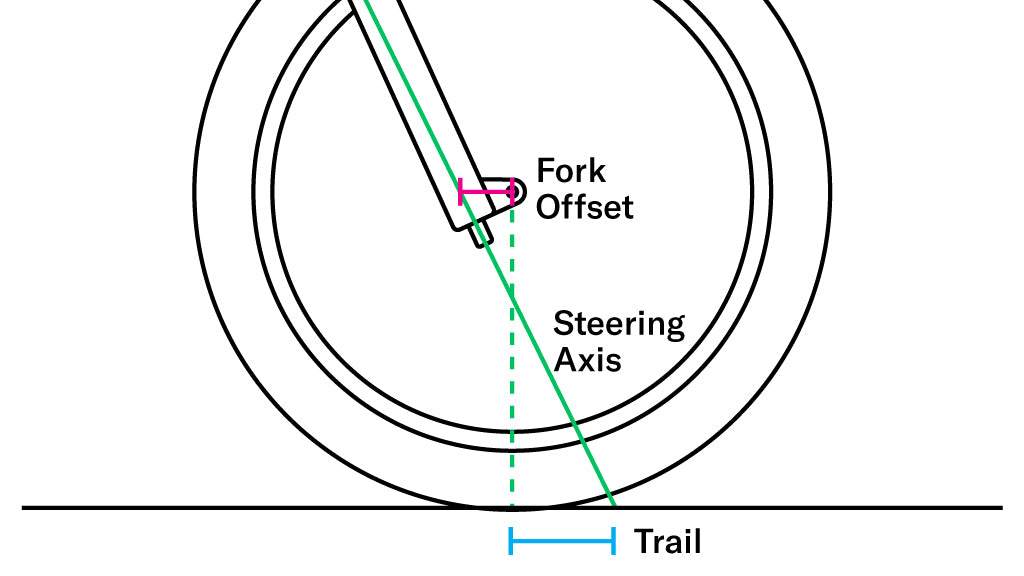

Fork offset is the distance between the front axle and the steering axis of the fork.

The diagram above shows how the front axle is offset so it is forward of the steering axis. This offset is measured in millimeters. Its purpose is to adjust the amount of 'trail' in the steering geometry. For 29" bikes, the 51mm offset fork has been the standard for nearly a decade.

The diagram above shows how the front axle is offset so it is forward of the steering axis. This offset is measured in millimeters. Its purpose is to adjust the amount of 'trail' in the steering geometry. For 29" bikes, the 51mm offset fork has been the standard for nearly a decade.

What is trail?

If you draw a line through the steering axis to the ground (as in the diagram above), trail is the distance from that point to where the front wheel touches the ground.

Trail is what makes the bike's front wheel self-straighten when it is moving forward. Think of the wheels of a shopping cart. They want to straighten when you push the cart forward. This same phenomenon occurs on your bike. It helps you stay upright when riding on two wheels.

Increasing trail improves straight-line stability. The front wheel feels harder to turn but also harder to knock off line.

Decreasing trail improves agility. The front wheel feels easier to turn and it can make a bike feel more nimble.

Trail on a mountain bike is affected by three factors: fork offset, wheel size, and head angle.

Reducing fork offset increases trail. Increasing fork offset reduces trail.

Larger wheels increase trail. With a larger wheel (e.g., a 29” wheel) the axle is higher off the ground compared to a smaller wheel. If you draw a line through the steering axis to the ground, it intersects the ground farther forward of the axle, increasing trail.

Slacker head tube angles increase trail. With a slacker head angle, the intersection of the steering axis and the ground is farther forward of the axle, increasing trail.

Increasing or decreasing trail too much makes a bike difficult to control. For mountain bikes, the sweet spot that provides a good balance between stability and agility is around 80-100mm of trail. Many mid-travel bikes settle near 90mm with a 51mm offset fork.

Why did 51mm offset forks become standard for 29” mountain bikes?

When 29ers first appeared, they didn’t catch on right away. 29ers had more trail due to the larger wheels and felt hard to turn compared to traditional 26" bikes. Mountain biking pioneer, Gary Fisher, found the handling of 29ers to be too slow and ponderous. He wanted to improve it with his new line of 29er mountain bikes in 2009/2010. These bikes introduced what Gary Fisher called “Genesis 2 (G2) Geometry.”

A 2009 Gary Fisher Superfly with a G2 (note the 'G2" on the fork lower) 51mm offset fork.

A 2009 Gary Fisher Superfly with a G2 (note the 'G2" on the fork lower) 51mm offset fork.

The defining feature of G2 Geometry was a fork with the offset increased to 51mm. Early 29er forks used the same offset as 26” forks (around the 40mm range) which contributed to the high trail numbers.

Mountain biking legend and product tester for Trek’s R&D department, Travis Brown, helped refine the offset used in Gary Fisher G2 Geometry bikes.

“We were trying to prove the credibility of 29ers and a big roadblock was the trail numbers,” says Brown. “People thought the head tube needed to be steep to maintain the trail figure we had already established for 26” bikes. This steep head angle was really preventing the category from moving forward. ”

Bike designers in the early 2000s tried making 29er head angles steeper to reduce trail so their bikes would have quick handling similar to 26” mountain bikes. This approach worked, but it sacrificed downhill performance. Steep headtubes made these bikes less stable. A lot of riders went over the bars on these bikes.

“We decided instead to engage in the offset variable because it allowed us to use a slacker head tube angle and still maintain a trail figure that was acceptable,” Brown explains. “You don’t lose any of the benefits a slack head tube provides for fast descending, but you still have a low trail number for handling tight corners.”

Why are bike designers now reducing fork offset?

Stability is the new prime goal of modern trail and enduro mountain bikes. To provide this stability, geometry has evolved so that new bikes have longer reaches, shorter stems, and slacker head angles. This gives riders great control and confidence when descending fast on steep terrain.

But the disadvantage of this new-school geometry is that the front wheel gets pushed farther forward of the rider. Because the front wheel is now so far in front of the bike’s center of gravity, it’s harder to maneuver in tight corners and get weight on the front wheel for traction.

“You need to learn to ride with your weight shifted more toward the front of the bike,” explains Isreal Romero of Mondraker bikes. Mondraker helped drive the development of longer bikes, and riders have since had to adapt.

“You have to be more aggressive with your weight positioning and actively push forward," Romero says. "This way you'll have more confidence in your front tire grip. The more aggressive you are and the faster you’ll go, the better the bike will ride. It might take a couple of rides, but once you get used to it, it will be natural.”

When things get steep and hairy, our instinct is to lean back, away from danger. But with a long and slack bike, you need to do the opposite and lean forward to maintain traction. It takes a lot more commitment, and these bikes will punish timid riders with a sudden loss of traction or by running wide.

Reduced-offset forks have promised to remedy this needy bike behavior. Reducing offset brings the front axle back closer to the rider. In theory, this should keep the wheelbase from getting too long for tight corners and make it easier for the rider to get weight on the front wheel.

A Transition Sentinel with a reduced offset fork.

A Transition Sentinel with a reduced offset fork.

Transition Bikes was one of the first major brands to tout the advantages of reduced offset forks with its “Speed Balanced Geometry (SBG),” which used shorter 42-44mm offset forks. Competitors followed suit and now several popular bikes come from the factory equipped with reduced offset forks.

Travis Brown has performed testing for Trek that supports the performance claims of these new reduced offset forks.

“When we did offset testing on forks, we wrapped the crowns so the field testers couldn’t tell what fork they were riding,” Brown says. “We do everything we can to prevent confirmation bias. We have some ongoing experiments with our riders now where they have been trending back toward shorter offsets."

“Now that the appetite for slack head angles has changed significantly for 29” bikes, we’re really reevaluating what the appropriate offset is," Brown says. "Sometimes I do think modern geometry has gone a bit too far with long reaches and slack head angles. Those bikes are very stable, but they have a narrow performance window. You have to ride them on really steep and fast terrain and be very aggressive to get the most out of them.

“But we’re discovering that a reduced offset fork can reign in these extreme traits a bit. It's easier to find traction in tight corners and through a bigger range of speeds.”

We know that trail is affected by offset, wheel size, and head angle. A 29” bike with a slack head angle already has a large amount of trail. So how can reducing fork offset and increasing trail improve cornering? On paper, it should make a bike harder to turn.

But, remember that riders need to shift more weight forward in order to corner well on long and slack bikes. Even though the actual steering geometry is more resistant to turning, reducing offset and increasing trail achieves the same result as the rider positioning their body farther forward. You are, in effect, achieving a better position and weight distribution for good cornering through geometry. Because the front wheel naturally maintains traction, it feels easier to attack corners.

This isn't a new idea, and motocross riders already discovered it years ago. Reducing fork offset had the same effect as moving the engine forward in the frame. Steering feels better because more of the bike’s weight is biased forward, keeping the front wheel planted. As with suspension, wide handlebars, and mullet wheel sizing, the mountain bike industry continues to apply lessons already learned with motorbikes.

There’s an additional benefit too. Trail shortens as a fork compresses (the head angle steepens). This makes a bike less stable when it’s deep in its travel. Because a reduced offset fork has more trail at full extension, it has more trail at full compression too. More stability deep in the travel is always a good trait to have for hard-hitting enduro and downhill bikes.

There’s an additional benefit too. Trail shortens as a fork compresses (the head angle steepens). This makes a bike less stable when it’s deep in its travel. Because a reduced offset fork has more trail at full extension, it has more trail at full compression too. More stability deep in the travel is always a good trait to have for hard-hitting enduro and downhill bikes.

44mm vs. 51mm offset forks: My experience

Many trail and enduro bikes are now designed around reduced 42-44mm offset forks. Reduced offset is less common for 27.5” bikes (for now) but some brands like Transition and Yeti are offering 27.5” models using reduced 37mm offset forks (27.5” bikes traditionally use 44-46mm offset forks).

If you want to purchase an aftermarket fork to experiment with, FOX produces reduced 44m offset forks and RockShox produces 42mm offset forks for 29” wheels; 37mm offset forks are available for 27.5” wheels.

The first reduced-offset fork I tried was an aftermarket 44mm offset FOX 36. While waiting for it to ship, I dreamed about how this fork would turn me into a cornering machine and help me destroy Strava PRs.

The first reduced-offset fork I tried was an aftermarket 44mm offset FOX 36. While waiting for it to ship, I dreamed about how this fork would turn me into a cornering machine and help me destroy Strava PRs.

After installing the fork, I was in for a rude awakening. Dropping into an extremely steep and technical local trail, I felt like I was struggling to dodge rocks and keep things under control. The subtle change in geometry made my timing feel slightly off. That first impression stuck with me.

I got used to it after a run or two and the bike soon felt normal. I rode the new fork for a total of eight months. Was I faster? My lackluster Strava times say not by much. Reducing the offset of my fork wasn’t a magic pill. If it improved my speed, it was marginal.

Even though I wasn't smashing Strava KOMs, the claimed traction benefits were still appreciable. I felt more stable and planted when I turned into corners. I’ve never been good at tight hairpin turns, and the reduced offset fork made me feel just a little more comfortable. In time, I became less scared of the front wheel washing and this helped me focus more on my positioning and technique through corners.

Practicing my cornering technique over the last couple of seasons has made the biggest difference in my overall speed. Perhaps the little extra traction I felt with the reduced-offset fork sped up the process. I think it can be a useful tool for improving confidence and honing your technique. (If you really want to improve your cornering, check out these tips from world-renowned mountain bike coach, Lee McCormack.)

So, switching to a reduced offset fork isn't going to be life-changing, but it’s still nice to have. What’s my recommendation? If you’re buying a new bike and cornering is your weakness, choosing a reduced offset fork can help. If you’re trying to race enduro or downhill competitively, a reduced offset fork can give you a slight edge.

Ultimately, I think reduced offset forks work best on longer and slacker bikes with big travel. The longer and slacker your bike is, the more you will notice the benefits of bringing the front wheel closer with a reduced offset fork. (I still favor 51mm offset forks on my XC race bikes because I want that style of bike to feel agile in race situations.)

If you don’t have a reduced offset fork on your bike right now, don’t lose sleep over it. On my last few bikes, I’ve swapped forks out several times between reduced 44m offset and 51mm offset forks. Each time I get used to the new offset within a few runs. In my experience, you simply adapt to whatever you’re using. If you practice enough with whatever you have, you will get faster. That's the truth.

My current enduro bike has a 51mm offset fork because The Pro’s Closet offered them at a great discount. I’m used to how it handles, and I see no reason to change it yet. I am sold on the idea of reduced offset forks, but since it's not life-changing, there's no need to spend money if your current set-up works fine. If my current fork gets damaged, or I decide to buy a new bike, I will choose a 42mm or 44mm offset fork just to give myself a little mental boost.

No matter what fork I'm on though, it will still be fun to ride!

Do you ride a reduced offset fork? What’s your experience been? Let us know in the comments!