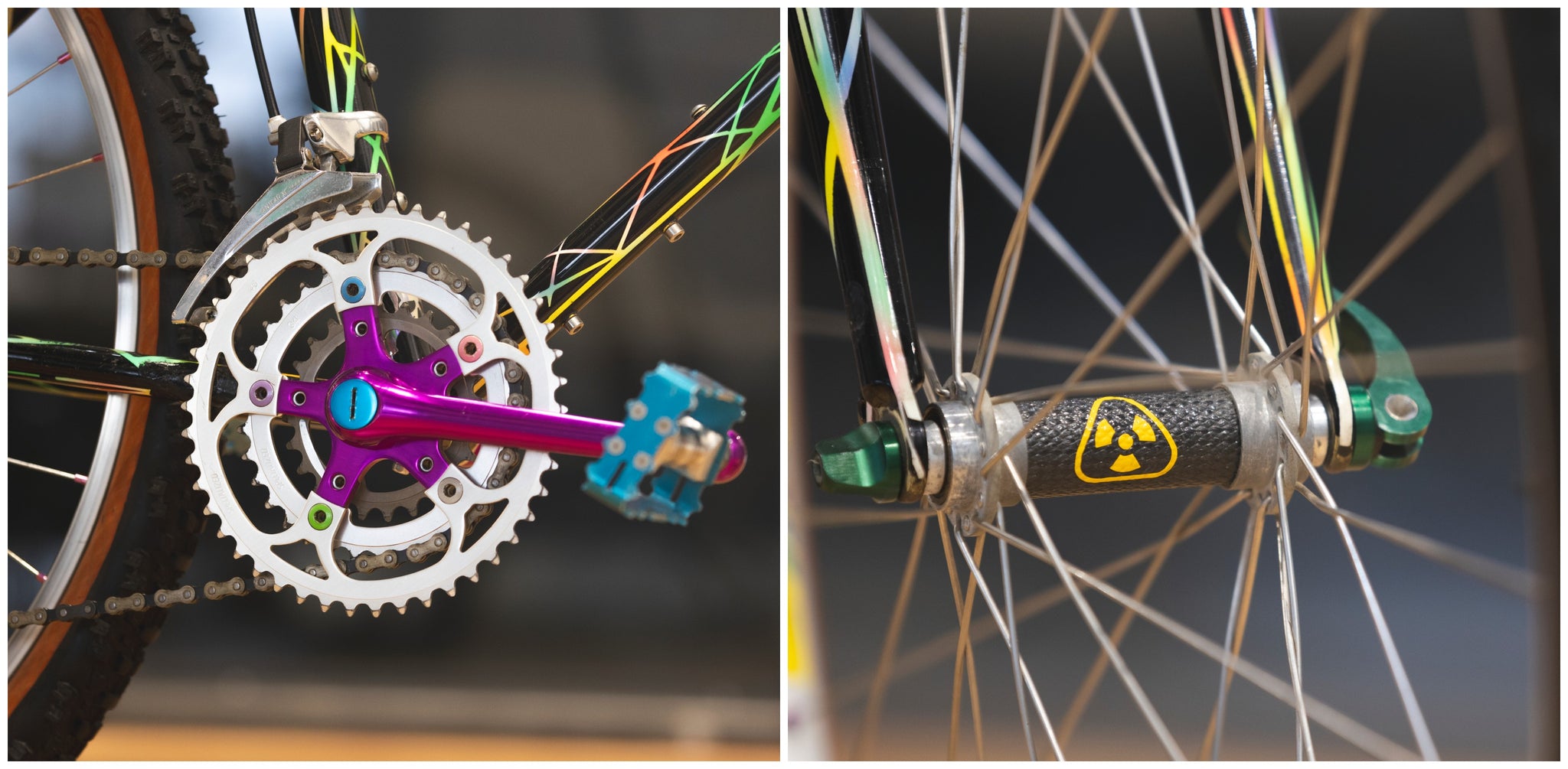

I put this Mantis X-Frame in the middle of the TPC retail store alongside a replica of one of Greg Lemond’s Tour de France-winning bikes and everyone who came in was more interested in the Mantis. It's not that surprising. If the bright multicolored paint or the purple anodized Cook Brothers cranks don’t grab your attention, then the wild X-shaped frame will.

What was surprising though is that no one who came in seemed to know anything about Mantis. This clearly means we need to stop and tell the story behind this bike!

The Mantis X-Frame comes from an era when mountain bike design still evolving and innovation was rampant. Ultimately, the X-Frame was an evolutionary dead end, but it’s fun to look back at how this branch of the fat tire family tree came to be.

[button]Shop Mountain Bikes[/button]

Mantis and MTB Pioneer Richard Cunningham

RC from the first issue of Mountain Bike Action magazine.

RC from the first issue of Mountain Bike Action magazine.

If you’ve been following the sport for a few decades, you likely have heard of Richard Cunningham (we’ll call him “RC”). He was the long-time editor of Mountain Bike Action Magazine and later the Technical Editor at Pinkbike until retiring in 2020.

Before working as a mountain bike journalist, RC designed and built mountain bikes as the founder of Mantis. He always loved tinkering with machines and in his youth, he’d gravitated toward motors. He owned his own machine shop, worked on Porsche 934s, and raced motorcycles.

In his mid-20s though, he grew concerned about the impact his interests were having on the environment. In an interview with Cynthia Ward, he said: “I knew that I didn't want to participate in that world anymore. There are enough people who make cars, enough people who think cars are the coolest things in the world. I wanted to do something that made a better world."

A 1983 Mantis XCR from the TPC Museum. Photo: Joey Schusler.

A 1983 Mantis XCR from the TPC Museum. Photo: Joey Schusler.

In time, that “something” became bikes. He took a job assembling Schwinn cruisers at a local bike shop. Then he had a stint building custom road racing bikes at Medici.

He got into road riding and eventually he began venturing off the pavement onto dirt roads and trails. This is what sparked his interest in fat tires and flat handlebars. After seeing one of the first mountain bikes from Tom Ritchey, he was inspired to build his own.

RC built his first Mantis in 1981. The story goes that this first attempt was a complete dud. His friend, Monte Ward, who tested it claimed it was the worst handling bike he’d ever ridden. But RC was undeterred. He was now hooked on mountain bikes, and he kept learning and improving.

In 1982 RC released the first Mantis catalog which included classic Mantis bikes like the Sherpa, XCR, and Overland.

[newsletter]

The Cantilever Mantis X-Frame

The Mantis X-Frame is the perfect example of RC's innovative thinking. It was built between 1987 and 1988 and it didn’t use the traditional diamond frame shape that most builders favored. Instead, RC designed a “cantilever” frame.

The Mantis X-Frame is the perfect example of RC's innovative thinking. It was built between 1987 and 1988 and it didn’t use the traditional diamond frame shape that most builders favored. Instead, RC designed a “cantilever” frame.

Some of the first mountain bikes actually used cantilever frames because they were based on classic Schwinn cruisers. But RC’s cantilever frame was a bit different from the classic cantilever design which used thick curved tubes.

Instead of explaining why RC built this bike, I figured I'd let the man himself do it. 10 years ago, TPC’s founder, Nick Martin, reached out to RC to get more details on a similar X-Frame he was rebuilding. RC told him the story of how this unique frame design came about:

Instead of explaining why RC built this bike, I figured I'd let the man himself do it. 10 years ago, TPC’s founder, Nick Martin, reached out to RC to get more details on a similar X-Frame he was rebuilding. RC told him the story of how this unique frame design came about:

Eddie Rea was my shop manager at Mantis and is one of my closest friends to this day. The non-elevated Valkyrie (we called them X-Frame) is the rare bird, as we only made a small number of them before I started to experiment with elevated chainstays and switched production to the E-version.

The idea for the X-Frame came from an invitation from Gary Fisher to fly up to his bike company and do destruction testing on his new Super Caliber frames which featured the revolutionary Tange Prestige heat-treated tubing. Gary was kind of angry because, as a contributor to MBA mag, I wrote that that particular frame buckled near the weld. The downtube must have not had a Tange DT, because when we pulled the fork towards the frame, the load cell ran up to about 700 pounds and then the frame tubes cracked open in three places as if they exploded.

We then tested an oversized aluminum frame and it went up to 900 pounds before it buckled. (A standard chromoly frame buckles at 300 to 400 pounds.) Gary had an old Schwinn Excelsior cruiser frame lying around, so just for kicks, we put the big steel fork on the Schwinn and loaded it up. It went to over 1,000 pounds and barely deflected when it failed. I went home thinking that if a cantilever frame made from one-inch water pipe could outperform a bunch of high-end mountain bikes, I should rethink the basic bike design.

RC said he started working on the X-Frame design on his flight home. He explained that the head tube junction of a classic diamond frame is its weakest point. After witnessing the strength of the Schwinn, he realized that triangulating the head tube area of a steel frame would allow the use of smaller, lighter-weight tubes and result in a frame that was much stronger than its predecessors.

RC said he started working on the X-Frame design on his flight home. He explained that the head tube junction of a classic diamond frame is its weakest point. After witnessing the strength of the Schwinn, he realized that triangulating the head tube area of a steel frame would allow the use of smaller, lighter-weight tubes and result in a frame that was much stronger than its predecessors.

So, the X-Frame used smaller, lighter main tubes, and x-braces. I configured the rear triangle to catch the X-tubes to make the stand-over height super low. The bikes worked well, in spite of the fact that the smaller main tubes made them laterally flexible. The Achilles heel was that V-brakes had not been invented yet and the cable routing had to go around the seat tube. Special care had to be taken to get the brakes to work correctly.

The BB was TIG welded because that was a big piece of metal and it made more sense, but I fillet brazed the rest of the frame myself, and at the time, I was really good at it, so I left the joints unfinished to lord this over the other builders of the time.

The first Mantis X-Frame was featured in the August 87 issue of Mountain Bike Action and prototypes were tested and raced at the NORBA Nationals. Only about 15-20 of these original X-Frames were made, which means the example we have is an exceedingly rare bike.

The 1990 Mantis Valkyrie in the TPC Museum.

Eventually, the X-Frame evolved into its final form: the Valkyrie. The key difference was the use of elevated chainstays. It used the same basic front triangle design, but elevating the chainstays away from the bottom bracket provided extra clearance:

We switched to elevated chainstays around 1989 as a work-around to escape the confinements imposed by narrow rear hub and bottom bracket standards of that period. Large-diameter chainrings and an inboard chain-line restricted the space available around the rear tire and the sprockets to a few millimeters for designers who wanted chainstays shorter than 17.5 inches. Redirecting the chainstays over the bottom bracket area eliminated those issues altogether and allowed us to use short stays and "big" tires without clearance problems — and to avoid frame damage due to chain fouling, which was then a common occurrence.

I'm not allowed to ride this particular X-Frame off-road (it's too rare!), but supposedly it was one of the best riding bikes of the time, offering a “magic carpet ride” that prevented you from getting too beat up on trails without sacrificing too much stiffness.

Evolutionary Dead Ends Are Still Cool

If we look around, we won't see any cantilever frames being sold. Instead, the mountain bike world is filled with the classic diamond-shaped frame and its various iterations. Ultimately, what the X-Frame "fixed" wasn't enough to overcome its weirdness. Simpler often wins at the end of the day.

I find it fitting that the X-Frame was fitted with WTB’s Roller Cam brakes, which suffered a similar fate.

These unique brakes were designed by another MTB pioneer and tinkerer, Charlie Cunningham (no relation). A triangular-shaped "cam" engages the brakes by spreading apart a set of rollers at the ends of the brake arms. Combined with repositioned brake bosses, the idea of the Roller Cam was to improve braking efficiency compared to traditional cantilever brakes. Ultimately, much like the X-Frame, they were just a bit too weird and complicated, and they faded away after the ‘80s as riders chose simpler designs.

These unique brakes were designed by another MTB pioneer and tinkerer, Charlie Cunningham (no relation). A triangular-shaped "cam" engages the brakes by spreading apart a set of rollers at the ends of the brake arms. Combined with repositioned brake bosses, the idea of the Roller Cam was to improve braking efficiency compared to traditional cantilever brakes. Ultimately, much like the X-Frame, they were just a bit too weird and complicated, and they faded away after the ‘80s as riders chose simpler designs.

While the Mantis X-Frame has no living descendants, it’s still a fascinating piece of mountain bike history. I love hearing about the train of thought that led RC to create it. He just wanted what every bike builder (and rider) wanted — a bike that was better, stronger, and faster. To that end, bike designers need to try things, experiment, and challenge the status quo. RC did that with the X-Frame, and many of his other innovative bikes.

RC with an early X-Frame. Photo courtesy of Second Spin Cycles.

RC with an early X-Frame. Photo courtesy of Second Spin Cycles.

RC explained it best:

When a sport first starts out, it's so new, just doing it is really fun. When I first started making mountain bikes, there were no boundaries. A mountain bike could be anything you could ride on the dirt. Nobody knew what made a good mountain bike, or what made a bad one. So I had a chance to experiment with different tubing, different types of arrangements that made a bike go faster or climb better, and it made a big difference each time I discovered something new. It wasn't just bicycles. I was participating with a very small group of other men and women who were making bicycles all over this country. We were creating a new sport.

[button]Shop Mountain Bikes[/button]